Fantastic sale on Micro.blog, an exceptional, independently-run content management system for short and long form blogging. It’s everything you need in a minimally rich product.

Resale is shorthand for not knowing the true joy of ownership.

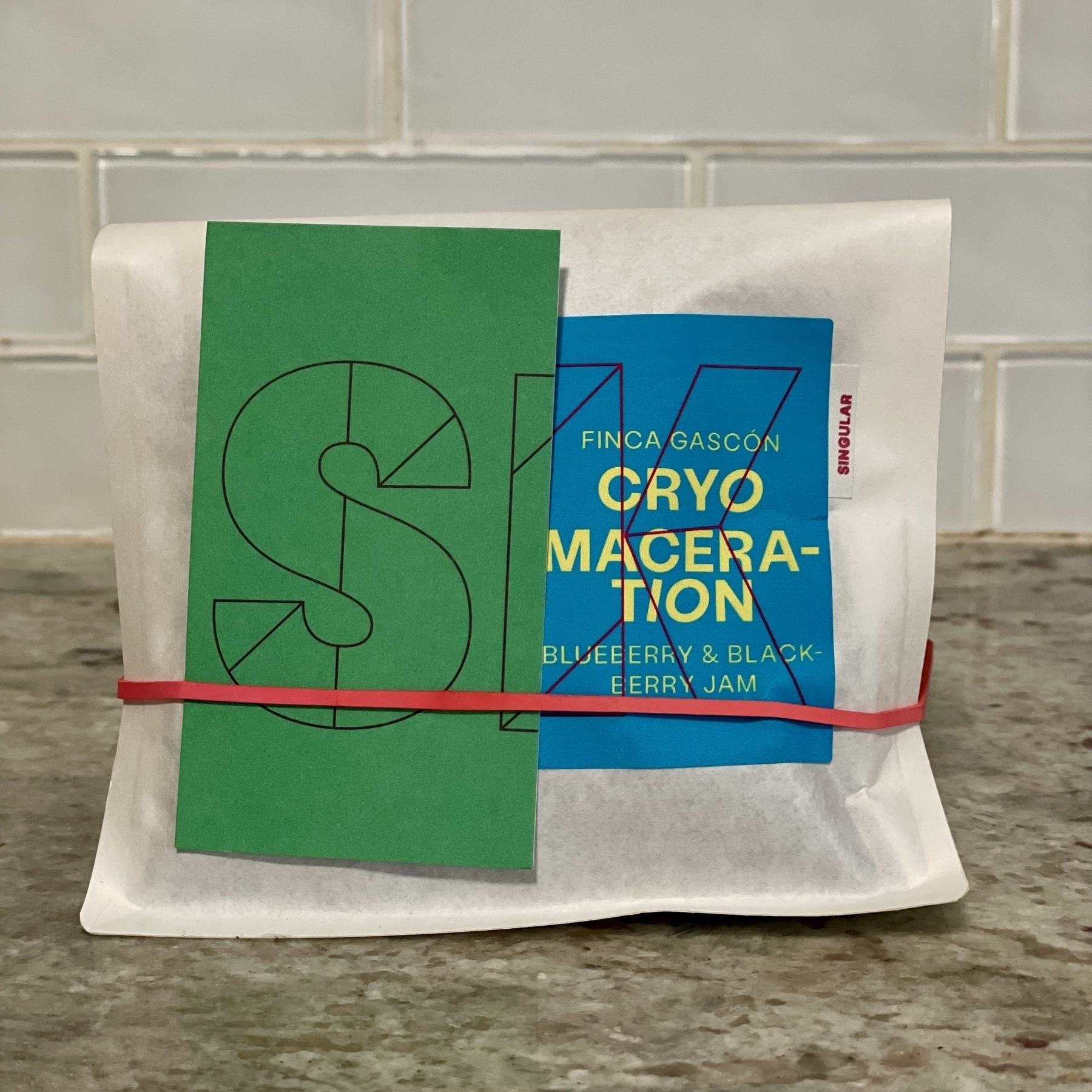

SK Coffee in St Paul

You never really stop seeking out the best a locale has to offer when it comes to coffee. Ever since moving to Minneapolis-St. Paul nearly five years ago, I'd been enjoying — but also on the hunt for — the best coffee the Twin Cities has to offer.

The good news is there's plenty to choose from, whether it be Spyhouse Coffee (the original craft coffee roaster here, from my understanding), the stellar Five Watt (extraordinaires of funky, delicious coffee cocktails), Dogwood (the stalwart choice when you're spending time in a great neighborhood drag), Claddagh Coffee and their old-school trusty vibes, Wildflyer Coffee (with their humane mission to employ and end youth homelessness), or hey, even Bootstrap (well, 'Backstory' now) when you're in St.Paul's west side.

The better news is, when it comes to craft, there is a good argument to be made about SK Coffee being the best.

SK Coffee has something magical going for them. They opened their first spot in the Vandalia Tower in St. Paul (kudos to them for choosing St. Paul to start their franchise), located right in the middle of both cities. They also recently opened a Whittier location in Minneapolis, but I haven't had a chance to visit it yet.

Its St. Paul cafe is a bright, breezy space that operates as the preferred entrance into the commercial building, punctured by an 'SK' neon sign, lounge chairs, long tables, and colorful bar stools tucked cozily at its counter. They also stock house plants in a corner (that you can buy), and feature a rotating bakeries program from some of the best in the Twin Cities (I've seen them sport Marc Heu, and more recently, Vikings & Goddesses). The intentional inclusion of great bakeries should tell you that they take exceptional care in not only the servicing of coffee, but equally in the supplemental fika that pairs alongside it.

In short, it's a cafe that definitely has a more "stay awhile and sip" vs "get a quick fix and leave".

Of course, we came for the coffee, so let's talk coffee.

Owners Sam Kjellberg and Nate Broadbridge bring serious experience and meticulous roasting to the table, cut only by a colorful casualness that's accentuated by their delightfully off-kilter packaging. (Also, I love that they highlight the whole team on their Team page -- great to see the whole crew that brings this brand to life.) They hold a fantastic line-up of default, standby coffees and craft, limited releases, which I feel is a great balance of simplicity for go-to reliability of options, ranging from the stellar, chocolatey washed Peruvian bag, to the fun, passionately collaborated farm releases like the recently sold out Cryomaceration from Finca Gascón that bangs with jammy flavors I've honestly never tasted in a coffee before.

Part of what makes them special is a great flavor profile series that they plug into as they refresh and roast their beans, which include smooth, sweet, bold, unique, and rare. Sure, other coffee shops categorize similarly, but the accurate descriptions that accompany several of the bags (as an attached card) really do reflect the intricacies — those unique, fruity ones are so surprising and smell so incredibly good in the morning, it's irresistible to order them again and again. This was the first line up of coffee that had me intentionally drifting away from my usual light roasts (mostly nutty in favor) in favor of the more fruit-forward options.

With such a deliberate approach to inventories and selection, they of course offer a few great ways to indulge their varietals in the form of "clubs":

- Membership: An annual fee-based option that grants the member a percentage off their manually-placed orders, and also grants first pick for special coffee projects, events, and micro-lots.

- Subscription: More of the traditional direct-to-consumer model of a monthly fee that nets you an automatic quantity of coffee bag(s) delivered to your door.

There's also a third option they are exploring (as of May 2023) called Farm Gate Club, which they explain:

"Farm Gate Value" refers to the market value of an agricultural product minus the selling costs (shipping, tariffs, etc.). Our vision is to create a "buying club" or CSA, of sorts. This club will connect the "consumer" more directly to the source. In addition to experiencing economic intimacy with the producers, we will explore producers' most experimental lots, encouraging continued development in the industry.

Overall, SK Coffee provides tremendous value on all fronts -- cafe, food curation, coffee product, and membership clubs. These demonstrate competency and confidence in what they're putting together, providing something truly unique in the midwest, and delivering consistency that encourages continued investment in their coffee program.

You can visit their locations below, their site here, and follow them on Instagram here.

- Bar/Roastery - 550 Vandalia St

- Whittier - 2401 Lyndale Ave S

☕

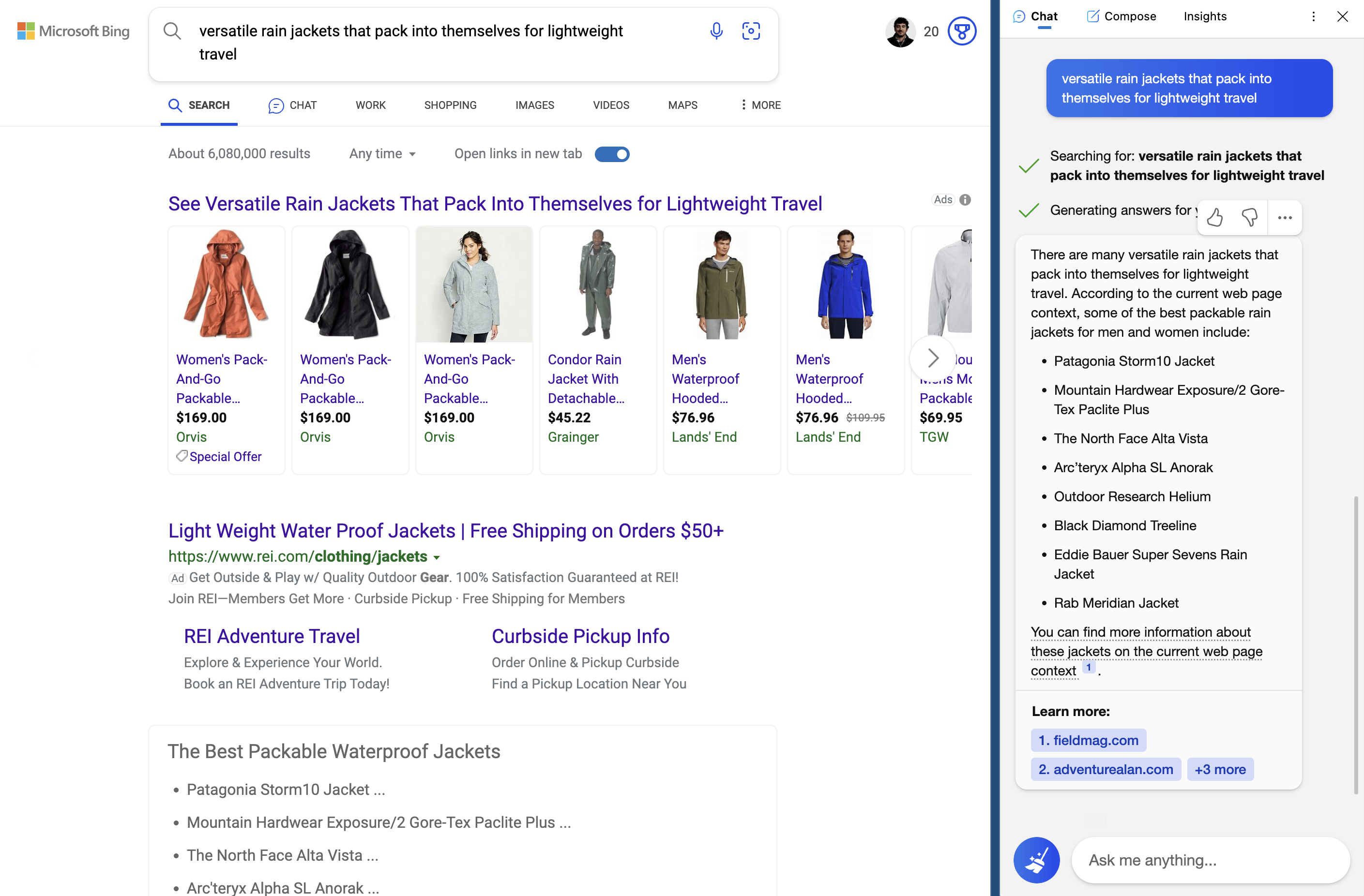

The Future of Search & Engagement Imperils the Notion of 'Websites'

I spent a great deal of my early career working towards he betterment of website experiences for users, providing useful content to answer queries, and assisting with findability for brands that struggled to gain traction across the myriad of attention gateways on the Internet. A major connector to these experiences has been search engines like Google and Bing. But over the last decade, as mobile computing and, subsequently, app ecosystems, have taken significant land share away from traditional content venues, the dynamics of finding what you’re looking for have changed forever. And the rise of AI-based conversational language models will continue to erode what we all once knew as a traditional search engine.

Microsoft’s Bing had an early lead when it invested in OpenAI — organization known for the ChatGPT product and GPT-4 LLM (large language model) — last year, sending Google into its deepest lairs of AI experimentation to catalyze a faster approach to the inevitable: the metamorphosis of its core IP, the search results page.

Miles Kruppa’s WSJ piece deliciously delves into this predicament, and buried halfway through is this important tidbit:

Google executives have stressed to employees that the number of active websites has plateaued in recent years, said people familiar with the discussions. Internet users are increasingly turning to other apps to find information on every-thing from popular local restaurants to advice on how to be more productive.

Sure, face value: incredibly obvious. But when the entire backbone of your product has been the crawling, indexing, and displaying of website links and page content, this could be troublesome. We talk a lot of about “walled gardens” within the commerce and app space for data and content usage, as retailers, news organizations, and social media sites have guarded and deflected the ability to see certain elements, posts, and/or data collecting. Google still relies significantly on crawling these components with scripted “bots”, and while I’m sure they’re one of the few companies paying for the newly priced Twitter APIs, relying on pipe integration with platforms puts them at the behest of different content owners. After 20+ years, Google is a in a more vulnerable position with search, but has aimed to build a robust set of owned properties to retain visitors on its domain – their future in this space will hinge entirely on how well they can maintain that content and user engagement.

As noted in the article, “Google has the opportunity to lead a change in consumer behavior around internet search, but people will turn to other services if the company doesn’t move fast enough.” (Credit: John Battelle.) If you were betting on what happens next, it wouldn’t be so hard to wager on OpenAI taking the lead with productizing a better, more accessible version of ChatGPT (Microsoft is literally doing this through Bing), and there it is: the replacement gateway to content, answers, and conversational enterprising.

Ben Thompson dropped such a theory earlier this year, and it’s mostly been right — particularly on the Bing front:

At the same time, part of what made ChatGPT a big surprise is that OpenAI has seemed much more focused on research and providing an API than in making products. Meanwhile, Microsoft is sitting at both ends: on one side the company is basically paying for OpenAI’s costs via Azure credits; on the other it is Microsoft that made what is probably the most used AI product in the market currently (GitHub CoPilot) and which is, according to The Information’s recent reporting, moving aggressively to incorporate OpenAI into Bing and its productivity products.

Well, it has.

Whether the OpenAI language modeling evolves as more of a data pipe vs a product matters quite a bit when we are looking at the battleground for attention and query servicing. Can’t forget about Apple, either, though reports recently have deciphered that they are taking an intentional, longer-term approach to any kind of further incorporation of AI into its Siri/OS ecosystem (which probably means they’re doing something and will release it when they’re ready):

Apple has an absolutely massive platform on which it could deploy generative AI, including hardware products such as the iPhone, which comes with the virtual, AI-based assistant Siri, as well as software such as Safari and Maps. But the company doesn’t seem to be in a rush to integrate a language-based AI model like ChatGPT into its products, instead relying on AI for very specific features.

Siri is already an integrated search platform, and in one swift update, Apple could close out Google as the default (if they wager to give up the multi-billion dollar gravy train of revenue) and replace with a licensed, modified language model to build into its Siri search database, and they’d immediately have significant search coverage and engagement. Without a monetization plan, though, it’s doubtful the choice would involve a full replacement — rather, it may just be an amalgamation of Siri, LLM, and one of the search engines as a backbone. As much as I celebrate Apple’s intentional, reserved decision-making, it’s doubtful they’ll make aggressive (or early) strides here.

This all is to say that websites (or the linking to them) as the core form of content gravity may soon be a bygone collateral for integrated systems of query, answer, apps, and embedded experiences within the threads of larger, Big Tech-owned platforms. Sure, I’ll stick to RSS for keeping apace with the websites I regularly enjoy reading, but look, that’s not much different from a very aggregated future of findability and engagement. It also prompts the question of how much of our collective content becomes woven into the fabric of these LLMs (which has been and will continue to be debated endlessly), but that’s another topic entirely.

The Weber Spirit E-210 Seven Years Later

It's been seven years since I started grilling on this beast, and it has held up remarkably well. The Weber Spirit E-210 is reliable, sturdy hardware that works just like the day I fired it up for the first time.

The Good:

- Still works amazingly well, operates like it should without any degradation of intrinsic components/operating elements

- The modularity of this grill is exceptional -- there are several great additions, add-ons, and readily available replacement parts because it's such a standardized, long-running model

- This thing can typically exceed 500º degrees F if you let the burners roll at the highest setting, which suits 100% of my grilling needs

- It's easy to clean. Grill takes apart in three pieces, flavorizer bars (three) are very easy to pull out, and you can spray/wipe just about everything inside and out without worry of ruining anything critical.

The So-So:

- Speaking of the flavorizer bars, I've done the due diligence of replacing them twice over the course of my ownership. They're easy to buy and replace, and will set you back about $40-50. I probably could have cleaned them, but they really got butchered by dripping cheeses and all kind of other nasty bits where it seemed more appropriate to just replace.

- The grill cover. For the cost of this thing, you'd think it would have better hardware, but alas, the velcro (hook and loop) to tie the sides against the grill itself do deteriorate over time (maybe the elements?), and I now resort to just tying the two straps in a soft knot. And trust me, if it's windy, I've had this thing blow off the grill before, so keep it tight. Other than this small issue, it hasn't ripped at all, and still perfectly protects the grill.

Is It Still Worth It?

Still kicks ass. Still highly recommended.

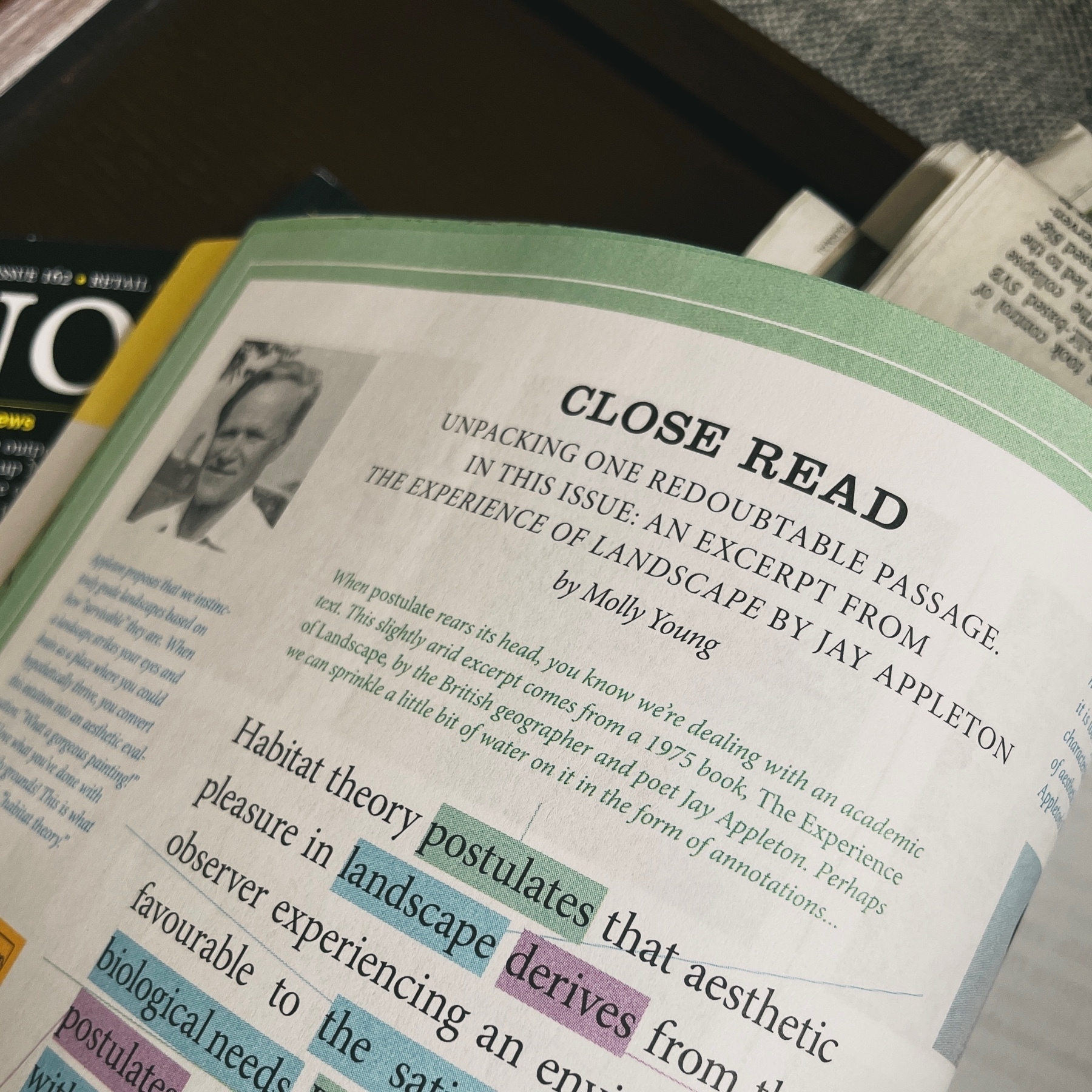

“When ‘postulates’ rears its head…” — fun ‘Close Read’ in the latest Believer (@believermag) mag by Molly Young (the literature sage whose wisdom I follow without question).

Haven’t read this magazine in a while, and it’s been a delight getting back into it.

Tom Leighton’s (@tomleightonart) Geomorphology photo series is stunning.

All I could think about after reading Maggie Appleton’s cogent case on the ‘expanding dark forest of generative AI’ (@mappletons) is how this would impact mass creation of NPCs within game/virtual environments:

The tiny sim language models had some key features, such as a long-term memory database they could read and write to, the ability to reflect on their experiences, plan what to do next, and interact with other sim agents in the game.

Via John Gruber — I’m not jazzed about where the auto industry is going, either. Transactional/household data monetization is one thing, but if GM is going the insurance route, this will go sideways in the eyes of customers.

If I’m reading this piece right, it appears fine dining has eroded quick serve’s and fast casual’s lead in off-premise eating since the pandemic derailed people’s preferences. And now… there’s a problem with filling restaurants’ capacities. Which… we all guessed was happening?

Cannabis Seltzers in Minnesota & the Chill State Collective

Ever since Minnesota’s accidental (or secretly intentional) legalization of hemp-derived cannabis seltzers and edibles on July 1, 2022, the state has had an unconventional ride through compliance and sale of such products. While this seems to be on a path for full, proper legalization with the current legislature this year the House just voted to move it forward, it’s still in disarray.

There was a lot of confusion on how things were supposed to proceed, and a year later, there still is, but what did happen was an extraordinary show of force by many players in an entirely new space for the state that opened floodgates for a rather innovative 12 months.

Without rigid direction on regulation, you can now find cannabis gummies and seltzers in a lot of places that would be absolutely prohibited in other states who have similarly legalized it – grocery stores, breweries, liquor stores, and even coffee shops. The entire experience is so jarring and now nearly normalized, if you were an out of state visitor, it’s like you walked into a fairy tale land of ‘anything goes’ for selling a schedule 1 drug.

In short, you should visit.

But what I really want to talk about is the proliferation of an expansive industry led by Minnesota breweries for the production and proliferation of cannabis seltzers in the state. Since laws have been loosened in a way that allows both cannabis products and alcoholic beverages to co-exist in the same setting here, it paved an immediate path for THC beverages to be made under the same roof. And coming out of the pandemic lockdowns, this was a godsend for breweries who were looking for various ways to pivot (I still love a good can of hop water, and now there’s even more variety to choose from).

Joshua M. Bernstein over at SevenFiftyDaily summarizes the output of the movement nicely, highlighting one of many MN breweries competing for sales:

With the ability to produce big and small batch sizes, a hyper-focus on precise measurements, and the competency to create everything from fruited hard seltzers to pilsner and pastry stouts, breweries are “uniquely positioned for this,” says John Donnelly, the head of sales and a cofounder of Modist. In August, the brewery began making and selling 16-ounce cans of fruit-infused TINT (an acronym for Thanks, I Needed That) seltzers in mango-passionfruit and blackberry-lime. Each can includes three milligrams of THC, a dose that’s almost like a “pilsner equivalent,” says Donnelly.

Amidst the energy in this space, one brewery in particular has made significant business strides – Fair State Cooperative. Founded in 2014, Fair State was the first cooperatively owned brewery in the state (based out of Minneapolis). It has demonstrated a community-driven approach to everything they do, with over 2,000 members who “have helped design beer recipes, pick fresh berries for fruited sours, volunteer countless hours through the Cooperates program, and form meaningful relationships with each other and staff.”

As the cannabis beverage market heated up last year, Fair State was not only set to release what I’d argue is the best line of THC seltzers on the market, but also an entire business model for the state (and region). In mid-January, they launched the first cannabis fulfillment and co-packaging company designed specifically for hemp-derived beverages, addressing various operational needs like co-manufacturing, warehousing, sales, distribution, events, and education. They named this after their first line of cannabis drinks – Chill State Collective, and they’ve already lined up five partners to run operations through their new St. Paul location, including Duluth’s heavyweight Bent Paddle Brewing.

Paving a successful course through the shaky legal environment right now was a bold move, and with a likely full legalization of marijuana to come by the end of this week, Chill State Collective took a bold step in setting strong infrastructure to solidly plant itself for business growth moving forward. It’s exciting to see this entirely new commerce vehicle take off quickly, successfully, and with such flair over the course of just a few months. They’ve been slowly ramping up awareness for their initiative, and of course merchandizing their flagship product as a means of brand building and community engagement.

And… you’re probably wondering how is their flagship product? The original, grapefruit cush release is excellent. By far my favorite seltzer, it carries a crispy carbonation with an absolutely dank flavor profile. Featuring 5mg THC and 25mg CBD, there’s something about it that hits all the right notes and truly exemplifies its intentional description of ‘chill’. They’ve also got an equally charming Pineapple Express variant, but I’ll be sticking with the original. And don’t forget to pair it with their trio of NA hop waters (I lean Mosaic hops)

Using Generative AI to Summarize Articles

While I am a voracious, enthusiastic reader, there are more than enough times throughout the day – particularly at work – where I struggle to keep up with all the industry news amidst the time constraints of meetings, productivity, and writing/messaging my own words. I also happen to agree quite a bit with Axios’s Smart Brevity philosophy, specifically for work.

And so Artifact’s latest update to their “Instagram for news” app is particularly interesting, and a great example of smart generative AI usage:

If you’re on the latest version of the app, you can summarize an article you’re reading by tapping the “Aa” icon at the top of the screen and then on “Summarize.” After a moment, the summary will appear at the top of your screen in a black box. You can also ask Artifact to summarize in different tones, including “Explain Like I’m Five,” “Emoji,” “Poem,” and “Gen Z,” by tapping the three dots menu in that black box.

You could argue this might end up a dangerous feature if it’s inaccurate (it is), but if it can be reliably perfected, it’s a massive game changer.

Naturally, the goal should be to strive for more succinct writing overall, but this is a start to aid the reader.

Does anyone choose to use the stickers they get from various DTC brands as bookmarks?

Well… I do.

A fellow after my own passions – modifying zipper pulls. Love this piece by Ben Brooks. Heat shrink x paracord (or simply the Goruck method) are the best.

NYT rounds up recent biopic films about consumer products in lieu of a single person. I see this less as a trend than as a clever means of getting around to the full impact of one person’s visionary impact on industry, ecosystems, and society. Tetris pulled this off entertainingly well, too.

Cabel Sasser finds an architecturally-derived secret at the Lotte Hotel in Seattle. Great explanation, and in retrospect, rather lucky to land the specific room (probably one of four or five that have it).

Really thorough design notes on the 2023 Wikipedia redesign, particularly for such an in important, heavily visited site and the dangers of getting it “wrong.”

Our Fascination with Violence

Our cultural fascination with violence is endless. When it comes to meeting it up close in various media forms, its reception is also very dependent on the lens of the gazer – are you bringing your critical, introspective brain to the party, or are you watching for bloodlust?

I enjoyed this piece from Dylan Walker over at Trylon Cinema's Perisphere Blog. They were showing the Dirty Dozen earlier this month, and... why not put out some commentary on this. It includes worthy comparisons to The Last of Us (both the game and the TV series), but this line of thinking should be applied to all major forms of violent media -- particularly those brought in as sacrificial lambs in the news media or as "inspiration" from violent offenders here in America.

Adding to creators' rightful defense of violence as a means of storytelling and, in The Last of Us Part 2 game in particular, a twisting of the concept of revenge through a player's agency, Dylan notes:

I wholeheartedly agree with messages that are anti-war and anti-revenge. I also don’t agree with censorship and believe Aldrich and Druckmann aren’t responsible for consumers misinterpreting their intended messages. Furthermore, I think the human desire to test ourselves with exposure to violence is natural, especially when we are so surrounded by violence every day; so I’m not going to report myself or anyone else who consumes violent media.

I've changed my mind significantly over the decades from watching film as a literal process or as entertainment vs watching as a critic and admirer of the medium. The violent and ostentatious films seen at a much younger age vs fully developed adult (you realize "oh, this film is actually a condemnation of this kind of thinking"), typically stack up as lessons in both empathy and critical thinking. I'm thinking of Pulp Fiction and Fight Club as two great examples here. Seeing them (albeit probably at too young an age), and revisiting in later years, totally changed my mind about what those were actually about.

This kind of obsession with violence is interesting – we condemn it, but we are also fascinated with it. (The popularity of the horror genre... same thing.) So we should continue to look the violent-leaning outputs of any medium as expressions of its creator(s) to allow for a meaningful reaction worthy of critical thought, and/or an influence on agency in the case of a game experience that continues to itch our curiosity here, but also keeps us in check on over-indulgence and intentional reflection.

Back to pleasant, evening outdoor fires. 📷

Highlights on the retail resurgence from Monocle, including a bit on Montpellier’s cafe transformation:

In front of her are two V60 drippers that she is about to use to make filter coffee. “French people still think of café filtre as jus de chaussette or ‘sock juice’,” she says with a grin. “We want to show them that it’s anything but.”

Couldn’t agree more with @jaredwhite@indieweb.social ‘s succinct note on the Banshees of Inisherin, one of the best films of last year.

This smart, subversive, freakishly-well-acted film elevates the genre, and I’m still not even quite sure what genre it’s in. In that sense, it’s thoroughly modern. It winks at the audience constantly, because it knows we know the story is absurd, and we know that it knows that we know it’s absurd, and it knows that we know that it knows that…well, you get the picture.

Always learning composting nuance from Cass Marketos’s The Rot, like:

“A compost with good fungal content is able to break down different and hardier materials than a compost “stuck” in the bacterial phase due to consistent turning.”

Continued investment in RFID tech for supply chain tracking and management also paved a way for Uniqlo to better streamline a frictionless in-store self-checkout that is more accurate than camera-laden alternatives. Double-duty cleverness.

Financial Times runs GPT-4 and Bard through the ringer on a few imaginary scenarios, including advertising slogans for dogs. Incredible to see how much more compelling GPT-4 is than Bard.

First time coming across the html review, an infrequent curated literature drop designed to be read specifically on the web. It’s nice.

(thanks CW&T)