A few recent reports on Facebook’s activities should have its users, policy makers, and technologists thinking constructively about how the company’s services should be perceived: is it high time to think about reasonable regulation, or should we let the titans roam free?

Why pick on Facebook? For one, they have nearly two billion active monthly users (according to Facebook, that is, a company whose numbers shouldn’t be accepted without some level of suspicion). That’s an immensely large swath of the planet’s Internet-connected population. And secondly, they — much like Google — earn an extraordinary stream of revenue from paid advertising, oftentimes inscrutable in its nature. To put things into perspective, Facebook netted $8.809 billion in the last quarter of 2016, 98% of which was derived from its advertising product. And I say this revenue is oftentimes inscrutable because while most users understand Facebook earns revenue off ads, little do they know how this product works. Users freely provide Facebook with data about themselves, and Facebook in turn provides that data to advertisers, publishers, and agencies so that these third-parties can target various formats of ads back at you (video, display/banner, post-click ad experiences) via your impressions, interactions, etc. It’s amazing how much money brands will pour into ads just to net an impression (really, an eye-glance) at an image. Money just pours into Facebook’s coffers off this “attention economy” methodology. (How many times a day do you check your news feed?)

Now that there is some context: Technology innovation and its subsequent ramifications for not only our data security and privacy, but also our very own thoughts and brain activity, are ripe for further progress and exploitation by large corporations. It is up to us to decide how far the reach of these technologies go, and what level of acceptability there is in their application and monetization.

Where Facebook Plans to Take Us

Facebook has made significant investments in what it calls Internet.org, a gigantic initiative to connect everyone in the world who doesn’t yet have an Internet connection. According to a profile on this initiative by Wired, the estimates are that 4.9 billion people as of 2016 are not connected. How exactly can Facebook pull this off? As Wired reports:

To reach everyone, Internet.org takes a multipronged approach. Facebook has hammered out business deals with phone carriers in various countries to make more than 300 stripped-down web services (including Facebook) available for free. Meanwhile, through a Google X–like R&D group called the Connectivity Lab, Facebook is developing new methods to deliver the net, including lasers, drones, and new artificial intelligence–enhanced software. Once the tech is built, a lot of it will be open-sourced so that others can commercialize it.

On the surface, this isn’t a conniving project. There are good intentions behind connecting humankind. And Facebook is investing money and resources into this project because they believe the world will be a better ecosystem when everyone is connected to the Internet. They also probably believe that those extra 4.9 billion people will join Facebook and contribute back to the investment by seeing millions of ads and pouring that investment back into Facebook’s pockets. This, too, is fine. It's business. But do the masses who will piggyback off this enterprise know that? And what hardware and software is Facebook aiming to develop for the next generation that will impact us, whether we’re using Facebook explicitly or not?

Let’s start with a simple one: Facebook’s advertising away from Facebook.com. This isn’t new. For about three years, Facebook has provided brands a product called Facebook Audience Network, a mobile platform that delivers ads to mobile apps and mobile sites across digital ecosystems. Google has had something like this for even longer (Google Display Network), but Facebook’s network has already reached second-largest, and has arguably better data to provide to publishers and agencies. Why and how does this correlate to Internet.org? Aside from being an ad service targeting its own users across their Facebook and non-Facebook activities, it’s also inherently built into future users’ Internet activities. This quote from a Business Insider piece says it all — Facebook ad executive Brian Boland describes Facebook Audience Network:

"For years, people externally would ask, 'Why aren't you doing an ad network?' We knew deep down that it was a good, important thing, but we really needed to figure out how to do it in a way that would bring what we did well to the rest of the internet."

Without reading too heavily into this, essentially Facebook, as we would have guessed, simply wants to provide the most personalized ads in the history of humankind to all of humankind wherever they might be. A grand concept with cosmic ambition.

And they aren’t stopping here. The Wall Street Journal reported on Tuesday that Facebook is testing a new means of helping media companies sell video advertising natively (on their own sites) in a smarter and more automatic way. This tool is called Audience Direct, and is Facebook’s push into media publishing houses to help re-affirm their relationships (since Instant Articles hasn’t been panning out all that well). It's also engaging media publishing’s Internet currency: earned attention from readers. We all know that video is an attention blackhole, so it was inevitable that Facebook would bring their personalized ad targeting to the masses through this medium.

As if Facebook following you to the far reaches of your online activities wasn’t enough, they announced at their F8 developers conference just this past week that they are “working to create a brain-computer interface that lets you type with your thoughts”. While Facebook has been throwing a lot of shit at the wall to see what sticks, this doesn’t smell bad to me. But it is one more thing we need to be apprehensive about before fully committing to whatever manifestation it ends up taking.

The brain-computer interface, as described by Facebook’s development team, “could be an ideal way to receive direct input from neural activity that would remove the need for augmented reality devices to track hand motions or other body movements”. It feels silly talking aloud to Siri or Google Assistant — especially in public — and that feeling probably won’t normalize. Facebook’s development in a neural interface is probably partially aimed at removing the public stigma of talking to computer assistants out loud, instead employing a conduit in your brain to do that same thing. As the Verge reports:

Dugan (Regina Dugan is one of the lead Facebook developers for the project) stresses that it’s not about invading your thoughts — an important disclaimer, given the public’s anxiety over privacy violations from social network’s as large as Facebook. Rather, “this is about decoding the words you’ve already decided to share by sending them to the speech center of your brain,” reads the company’s official announcement. “Think of it like this: You take many photos and choose to share only some of them. Similarly, you have many thoughts and choose to share only some of them.”

Being able to pull off this interface seems to require some level of mind-reading, just like Amazon’s Echo devices and Google’s Google Home devices require some level of constant listening in your home to be able to recognize keywords to initiate their services. It is actually a good thing that Facebook is declaring its long-term intentions ahead of this interface becoming reality. We as a people need to understand the ramifications of this kind of progress, and how invasive the future of technology could be.

But let’s remind ourselves that Facebook doesn’t make money off hardware (okay, maybe a tiny amount from Oculus Rift) or services (okay, that 2% of revenue from Facebook games) — they make money from selling ads. And it’s very indicative, at least right now, how Facebook would monetize something like this. Per an investigative piece from Sam Biddle at The Intercept:

Facebook was clearly prepared to face at least some questions about the privacy impact of using the brain as an input source. So, then, a fair question even for this nascent technology is whether it too will be part of the company’s mammoth advertising machine, and I asked Facebook precisely that on the day the tech was announced: Is Facebook able to, as of right now, make a commitment that user brain activity will not be used in any way for advertising purposes of any kind?

Facebook spokesperson Ha Thai replied so esoterically that Sam had to rephrase the question, to which Ha Thai simply reiterated that “privacy will be built into this system, as every Facebook effort” and “that’s the best answer I can provide as of right now”. Sam goes on to ruminate on this technology and Facebook’s somewhat careless response to his inquiry, mockingly pointing out that “Facebook’s announcement made it seem as if your brain has simple privacy settings like Facebook’s website does”. This likely isn’t true, unless they’re trying to build in neural obfuscations to parts of your brain and only permitting activity through the speech center. I’m not a neurologist, so any speculation here is out of my realm. But the idea of sending brain activity to Facebook’s servers for processing is a heavy concession to make when and if we all adopt this invisible interface. It does sound amazing and seamless, but coming from Facebook, the data we provide also sounds ripe for re-application and distribution to third-parties for monetization and security exposure.

Where & How Do We Begin Regulating?

We can’t progress technologically without violating (or re-wiring our perception of) a few privacy concerns here and there. And Facebook, along with many other technology companies, have the right to invest, research, and build solutions that further us culturally and technologically. But there are very important considerations we need to keep in check, primarily with regards to our inherent right to privacy.

In a recent piece on smart homes (starring tech like Amazon’s Alexa and Google’s Google Home) by Paul Sarconi for Wired, there is a “note” about privacy:

If your paramount concern in life is privacy, turn back now. Google Home and Amazon Echo are constantly listening, and they send some of what you say back to the mothership. But you know what? This is just another scootch down the slippery slope you stepped on when you signed up for Facebook, bought your first book on Amazon, and typed “symptoms of shingles” into a search box. Tech companies have always asked us to give up a little privacy, a little data, in exchange for their wondrous services. Maybe homebots are the breaking point. But the things Alexa can do — so convenient! One bit of advice: Before the gang shows up to plan the casino heist, hit the device’s mute button.

Sure, it’s a note that reads like: yeah, this is all great but you are no longer in control of your data exhaust, your digital communications, your shared and stored photos, your behavior and spoken words in your own home, but the superpower convenience of kindly asking Alexa to order new deodorant is too tempting to dismiss.

So where and how, indeed, do we begin talking about regulation? This isn’t about stifling innovation. I still dream about hovercrafts. But I am talking about process transparency and clarity of intent. It is inevitable that all companies will continue to mine, test, and use data for all kinds of innovations that make their way into products and services we’ll all use to make our lives better and more convenient. But if we don’t have an understanding of what we’re signing up for in terms and conditions of services we use, the implications of digital storage for notes and photos and communications with friends, or how using a device’s conveniences will require forfeiting our privately spoken words and thoughts, then we put more vulnerabilities into not only the hands of corporations, but also of governments and more malicious groups that could aim to hack and compromise that data. Without transparency into how this data is provided, accessed, secured, and shared, we shouldn’t feel confident in continuing to invest our dollars and attention into these companies’ products and services.

In his last article before retirement, the personal technology writer Walt Mossberg declares a call to action to which we all should attentively listen:

My best answer is that, if we are really going to turn over our homes, our cars, our health, and more to private tech companies, on a scale never imagined, we need much, much stronger standards for security and privacy than now exist. Especially in the US, it’s time to stop dancing around the privacy and security issues and pass real, binding laws.

Image of Fargo at Sunset from Jasper Hotel

Image of Fargo at Sunset from Jasper Hotel

The neon sign inside Empire Liquors Bar

The neon sign inside Empire Liquors Bar

The Bernbaum's Signage

The Bernbaum's Signage

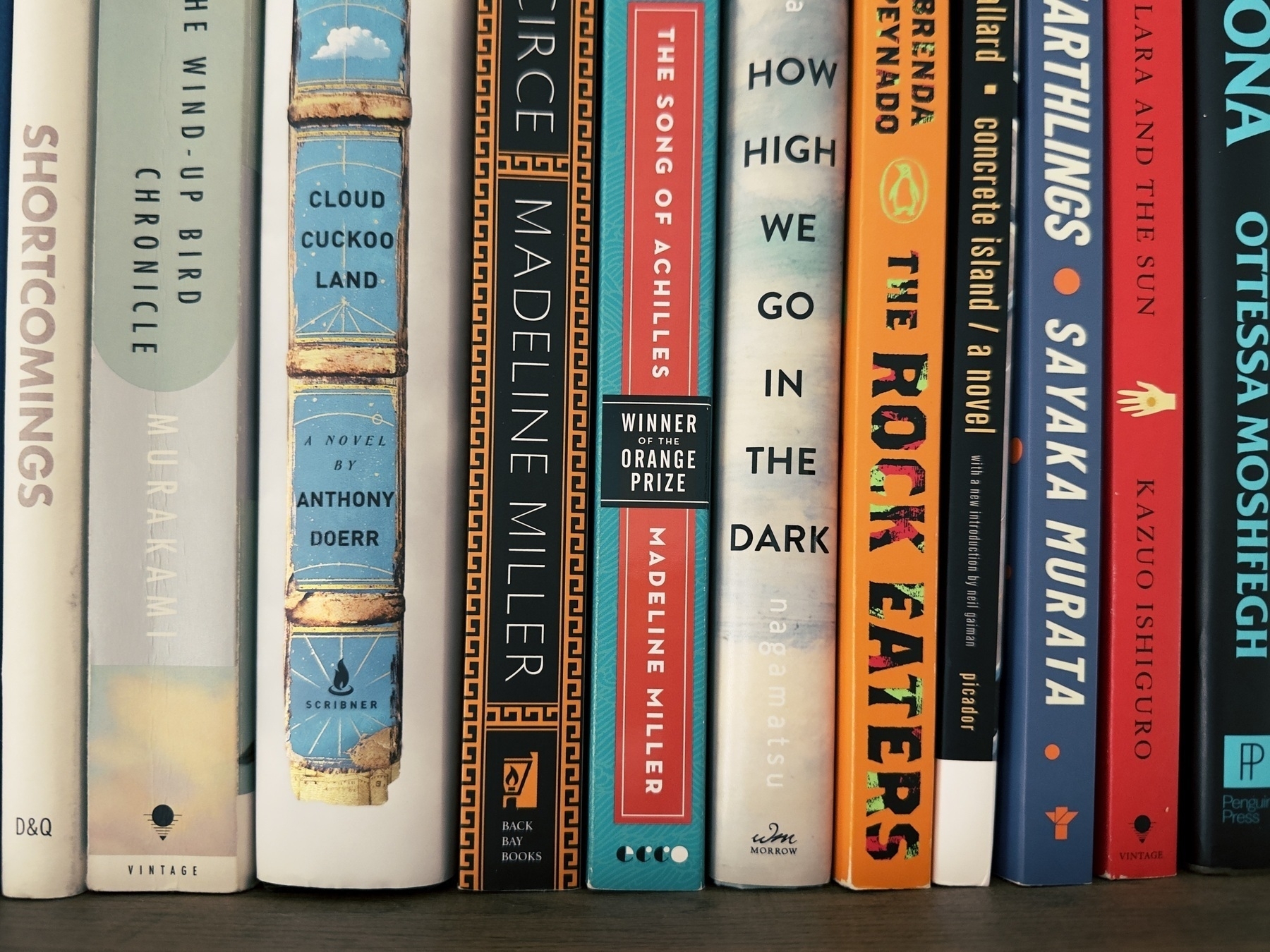

Inside Zandbroz Variety bookstore

Inside Zandbroz Variety bookstore