Great to see the push for a front-runner 3D scene standardization (USD) and its adoption by the important players in the space. Couldn’t think of a better partnership than Apple and Pixar.

Encountered a treasure chest in the neighborhood. Didn’t have the guts to open it.

Real-life Twisted Metal in Mexico. Absolutely wild what the drug war has wrought.

Fascinating global race for lithium battery recycling and closed-loop supply chains. USA is getting an injection of action from an Inflation Reduction Act clause, which should mitigate an over-reliance on China.

Another cinema rant: Khoi Vinh observes Wes Anderson like he truly is, for better or worse:

Anderson is essentially a children’s storyteller. For my money, he’s most at home when he’s telling stories through the lens of child characters

I haven’t seen Asteroid City (honestly, not planning on it). But… Barbie and Oppenheimer were fantastic.

We’re finally starting to see a contraction towards pragmatic efficiency in the VC market.

Globally, venture-capital investment in the first half of this year was $144bn, less than half of the $293bn raised by startups in the same period in 2022. Companies that do manage to raise funds are seeing their valuations squeezed.

This shouldn’t be seen as a trend — doing more with less is accelerating as a result of factors like AI usage and Wall Street favoring profitability vs unsustainable growth.

While I enjoyed Oppenheimer, Keith Harris’s full review here helps solve my askew feelings about it.

Pleasantly surprised to see dismantling innovation in the scrapyards business.

…the firm will build something that looks much like a modern car-assembly line, but which runs backwards. When an end-of-life-vehicle arrives, it is assessed for parts that could be reused or refurbished, the details of which go into an elaborate computer system which oversees the entire process.

Anne Helen Petersen reads an academic paper, and then pontificates (in a good way) on the hell of home ownership and the specter of its gradual decay into homogeneity.

It’s super fucking annoying that you can do the work of distancing yourself from one gaze without realizing the ways in which another one is quietly setting up shop in its vacant home.

The sage keeps on keeping on. 🌱

Breathing New Life Into the Weber Spirit E-210 Grill

I’ve been using this thing for going on 7+ years now, and as I’ve noted in the past, it keeps on performing. Recently, I picked up a QuliMetal cast iron grill griddle, built for various Weber models including my own. Why?

- This one was available to buy immediately versus the official Weber one

- Its portfolio of similar products had received great, genuine (sounding) reviews

- Moreover, I wanted to use a griddle on my grill, and I wanted to do it now

For the last several years, we had been bringing out a cast iron pan and setting it atop the slated grill currently built into the Weber to cook various meats, including salmon and steaks. This has been working fairly well, but bringing a pan out to the grill and setting it atop a grate that separates the cast iron from direct flame seemed inefficient and a lousy way of heating the vessel (which is absolutely required for searing meats). And secondly, if we were to use the original slatted grate to cook a steak on, for instance, there’s zero chance of providing each side a comprehensive sear — you have to settle for grill lines.

I’ll admit these reasons may not satisfy under scrutiny, but they’re the primary drivers for investing in this new piece of hardware. And as a bonus, I get to use the flat top griddle for diner-style smashed patties, eggs, bacon, etc. without resorting to polluting the air quality in our home (of which is something we're ever more conscious). Besides, grilling is one of the best things to do in the summer. I’d rather get more use from it and be outdoors.

So how does it perform? In as few words as possible:

- It does a fine job.

- It requires aggressive scraping and scrubbing to clear the debris and grease from it after use, but so does a cast iron pan

- I'm wagering I'll need to re-season it throughout its usage, but to me this still seems very much worth it.

- The first sears of a steak were, as anticipated, much better than what I was netting with the cast iron pan. Just need to dial in the timing and heat application.

Buying it was a good bet, and highly recommended if you're looking to do something similar here. Cheers. 👨🍳

Throwing this out here again – ooh.directory is a magical place to find writers, bloggers, and Internet folk that aren’t as visible on social stages like Instagram, YouTube, etc. Drop a dozen new URLs into your RSS reader, and you’re set for a revamped reading curriculum.

🌱 Not sure what kind of carrot we grew here…

Jason Fried has an encouraging piece about who and why you do business with selective companies, and not others. Locality should continue to play an integral role in these decisions as well, obviously!

Reworked the fence gates with very direct instructions.

(If you’re interested in these, you can get the Pull on here, and Push one here.)

Willamette Valley Wine Country is Worth the Trip

One of the first forays into our Pacific Northwest trip last month was Willamette Valley, sprawling out just south of Portland. It was a beautiful stretch of rolling hillsides, valleys, farmland, easily escapable territory from the urban cityscape in less than 40 minutes. (Having lived in Chicago for 15 years before migrating to a smaller city, I appreciate every time the speed at which you get to countryside in smaller urban environments.) It doesn't hurt that you've got the mountainous terrain in the horizon as you weave up and down the dusty roads -- it's peak west coast picturesque.

But First, the 'Fruit Loop'

Before we hit wine country, though, we did a circular jaunt around what's referred to as the 'Fruit Loop', a trail of farms and orchards (and some vineyards) that run up along the Washington-Oregon border, mainly running a southern trail from Hood River. I won't write like I know anything about this area, but... it was a very pleasant drive along the massive borderline trench that is the Columbia River -- truly stunning, and worth the drive alone.

The Fruit Loop itself was slightly underwhelming, apart from Mt. Hood lurking in the distance and a few pretty farm scenes at the two stops we made (Draper Girls for cider, and Packer Orchards for a milkshake and crackers). We appreciated the strong Oregonian agritourism present and thriving at these farms, and if anything else, this short trip functioned as a teaser to Willamette Valley.

Willamette Valley Wine & Hospitality

I don't know what I was expecting with a proper wine valley excursion, but I definitely loved what it was: dozens of vineyards weaving in and around lovely spots like the Dundee Hills and charming towns like Newberg, McMinnville, and Carlton (obviously calling out the ones we visited). There's just nothing like this out in the midwest (and yes, we have vineyards out here).

From the little knowledge I have of wine regions, Willamette Valley is highly concentrated (and perfect for) Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs, much of what this region is known for. I've over-indexed on heavier wines in my diet, so this was certainly going to be an exploratory experience for my taste buds. And I was pleasantly surprised by the variety and depth of what I had erroneously dismissed as lighter fare — there is plenty to love here.

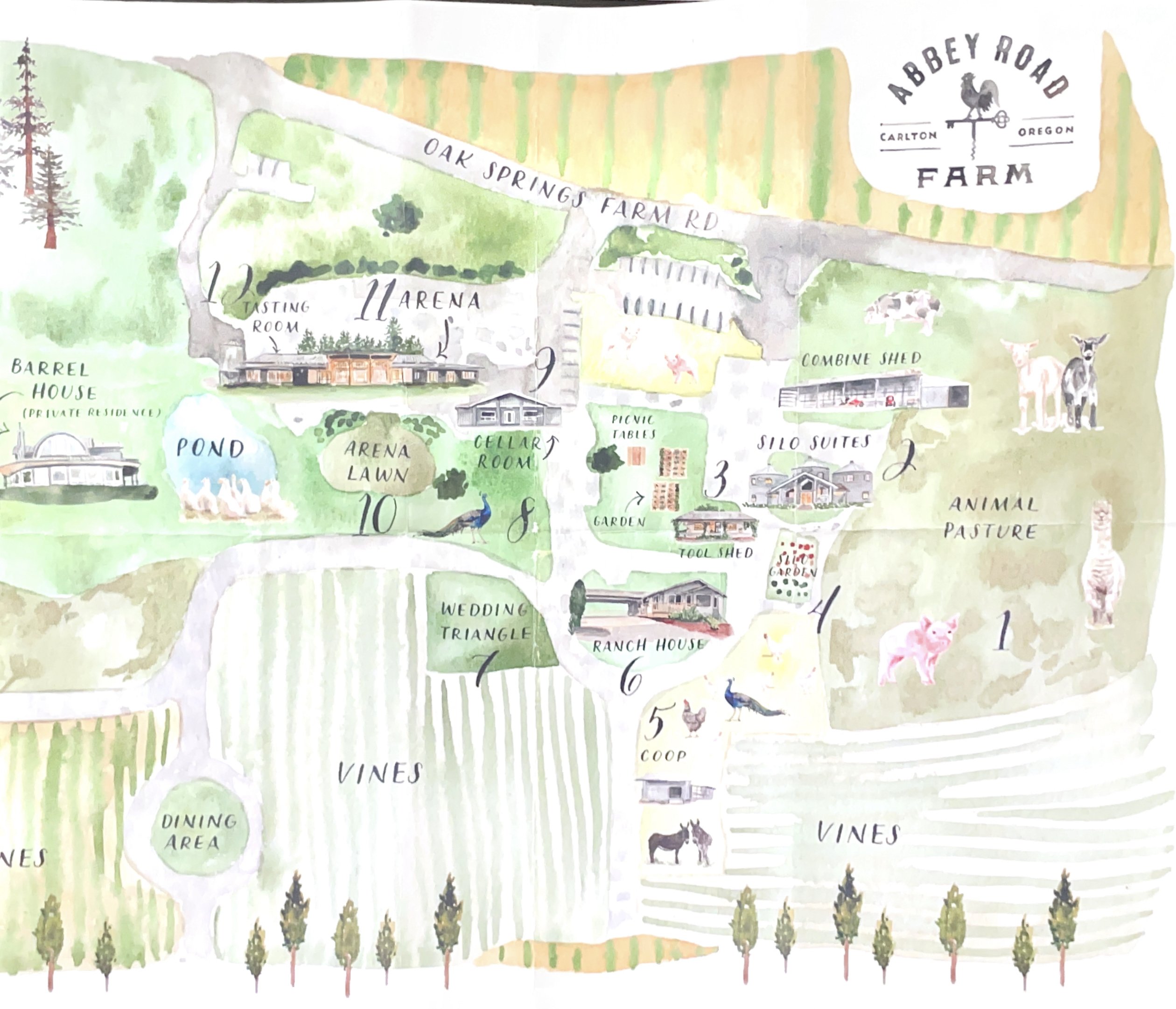

Abby Road Farm, Argyle, Domain Serene

Our first stay was Abby Road Farm, a multi-acre beauty accessible by dirt road that reused three silos to fit in a half dozen or so very comfortable rooms. Pigs, chickens, goats, birds (even peacocks!) roamed the campus, which also included dining patio, wine tasting room (with their own wine, which also is complementary with a stay), and plenty of well-designed settings to explore where they host weddings and other events.

It was remarkably well-tended, and notably served an excellent multi-course breakfast that shouldn't be missed. We spent time wandering around the campus, visiting animals, tasting wine, taking a few Polaroids, and enjoying the sunset. The night we stayed here was preceded by a few vineyard appointments, so we were feeling delightfully buzzed.

Our first stop had been Argyle, cabbed in by an Uber driver who also happened to have worked the reception at Argyle prior. This place felt corporate right off the landing: bustling with patrons, well-run operations, tightly curated menu, but overall, the tasting felt rushed and without much guidance or attention (which was fine to start out our foray into tastings).

We were placed in a nice corner spot and tried four glasses of bubbles, only a couple of which popped off exceptionally well — the other two came off a bit flat (but I argue my crappy taste buds aren't exactly forgiving, so bear with me).

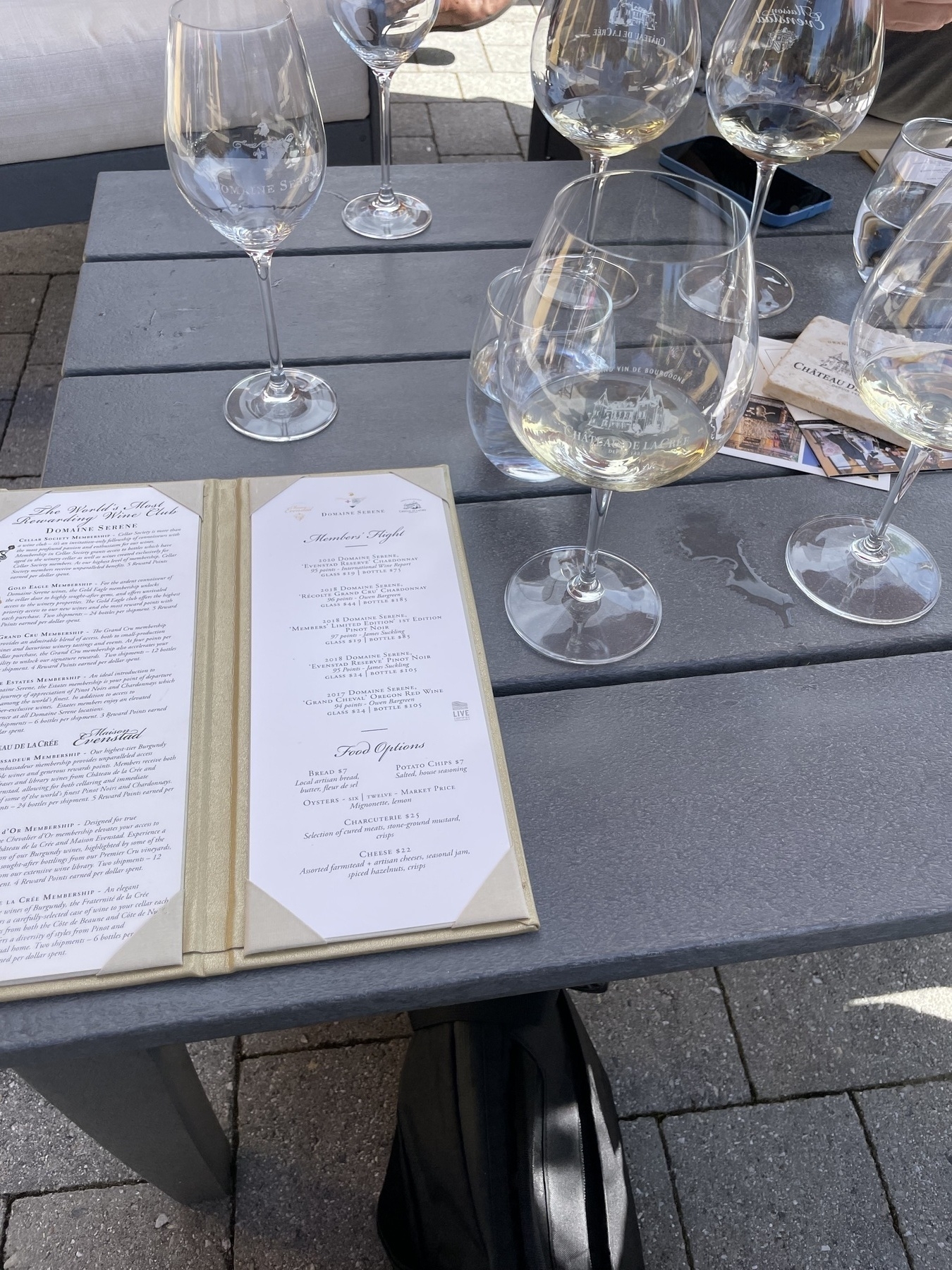

We picked up a couple bottles to go before getting scooped up by our friend, who proceeded to take us to Domain Serene.

As we approached the Tuscan-inspired clubhouse at the summit of a Dundee hill, we felt this place much better reflected our vision for what wine country would feel like (comparatively... Argyle, as nice as the facility was, is seated on a bustling street in downtown Dundee).

Admittedly, this place was an amazing, much more attentive experience. Extraordinary wines, the sommelier (Alex) was perfectly on point for walking us through pairings (two at a time, gave us context, let us taste ourselves). We moved through several (several) glasses of wine accompanied by kumamoto oysters and house-made potato chips, a near-perfect combination.

Afterwards, we wandered the surrounding campus, sipping a glass (I can't rightly remember what of) before heading back to Abby Farm Road.

The Black Walnut, Roco Winery

The second stay in the area was the up-high, breezy Black Walnut, a stately grouping of a dozen or so units atop one of the highest Dundee hills overlooking a swath of wine county. Quite a different vibe than Abby Farm Road, but not in any way more ostentatious — it flexed a broad courtyard dividing the primary hotel housing from a steeped double-unit building (in which we stayed), flexed plenty of seats and a fire pit overlooking a vista view in the back, and a sizable dining area instead with seat-yourself casualness in the mornings for breakfast.

And breakfast here was equally great: choose what you want from a tight menu of farm-focused meals, or set a time for a tasting menu (lunch/dinner), which unfortunately wasn't available during the days of the week we were there. Though it's stated in the name of the place that it's a vineyard, they don't actually produce wine at Black Walnut, but rather supply the grapes to a sister winery, The Four Graces.

Next, we visited Roco Winery as our only appointment for the day, but we really liked this one. A much smaller, but exceptionally genuine spot that had a "visiting your neighbor's vineyard" feel. A few tables out on a cozy patio under a perfect afternoon sun was the right way to spend a few hours.

After roving through a solid set of tastings, we scooped up a couple bottles (including a favorite Pinot called The Stalker), and headed out to prep for the evening dinner over at Earth & Sea in Carlton, following by enjoying a bottle of Roco bubbles up top the hill at Black Walnut while the sun set.

Willamette Valley was enjoyed a tremendous amount more than we anticipated, and setting wine appointments in the future as part of our vow for more intentional traveling is going to play out nicely, though it'll be key to ship back the bottles we get instead of draining them all on the trip as we go, but...

Nice to see Japan Airlines’ sustainable traveling push (by way of carbon reduction) by encouraging passengers bring only essentials and rent their wardrobe upon arrival, which is sourced by second-hand stores and excess retailer inventory.

The Tom Bihn Store

When we were planning our Pacific Northwest crawl and decided to head into Seattle for a few days to visit family, it was an inevitability that there would be a stop into the manufacturing facility (plus embedded retail store) of one my favorite bag brands, Tom Bihn.

Located south of downtown Seattle in the Industrial District, Tom Bihn sits inside a long building housing a number of other functions, like Two Beers Brewing Co., Fulcrum Coffee Roasters, and Seattle Cider. It's a quiet little spot amidst the bustle of trucks moving in and out of the area. All of Tom Bihn's bag manufacturing happens here, so there's significant space in the building to accommodate the materials and sewing of products. But they're also open Monday through Friday from 6:30 am - 3:00pm ("more or less") for walk-ins to check the place out and peruse available goods. All the items in the corner shop are the same ones tied to their website inventory, so you know exactly what to expect.

When we stepped inside, a fellow named Cody emerged from the manufacturing floor and greeted us. He happened to the same person who helped my wife get a faster delivery of her new Synik 30 bag in time for this very trip, so it was perfect that he was there the day we visited. The store is really just a few peg walls and a long table cutting through the middle of the space, where Cody brought in and laid out a few items in which we were interested in seeing various colors.

They've also set up a vertical mirror for you to check the fit and style on your person, and covered the border of it with customers' submitted photos of sporting their bags all around the world. Felt very restaurant 90s, and I loved it.

Ashley decided on picking up a Side Hustle in Ursa Ballistic, which ended up as a perfect travel companion as we marauded up the rest of the west coast into British Columbia. If you're a Tom Bihn fan, it's absolutely worth the trip into their HQ, even if you end up just getting a few more of their endlessly useful swivel double-carabiners. And if you're in the area, curious about quality, USA-built bags for almost any context, it's definitely worth the visit. I only wish we had more time to ask for a full tour of the facility and to check out the really neat fabrics/materials they have on deck (like Halcyon).

A vastly important federal push for reducing reliance on foreign sources for battery materials by mining here in the US could prove key during the election cycle, plus ensuring self-reliance as we pace to an EV-dominated future. I just hope they thread the needle on environmental regulation.

Curious to see how this pans out in court, but the FTC suing Amazon for “allegedly duping millions into enrolling in its Prime service” appears to be the most significant (and first?) trial of ‘dark pattern design’ on the Internet.

Negotiating with AI companies for licensing IP to be fed into LLMs is a slippery slope, especially since fundamental components of those models were already informed by mass website data scraping. I’d be quite surprised to see this shake out in anyone’s favor other than for AI tech.

Truly, a masterful multi-year run as not only the best, accessible gateway into Reddit, but also an exemplary designed app experience — Apollo will be missed.

Om’s darkly acute perspective on the future:

…as a society, the idea of what a human-to-human social fabric is has been breaking down for quite a while — especially as our idea of work has been redefined. Whether it is a lack of permanence or changing economic reality, work is a reality that triggers change. As uncertainty increases, we rearrange the jigsaw pieces of our lives.

Plenty to say and share (in the coming weeks) on the incredible wine country, seafood, and natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest as we head into the last stretch of our trip.

Until then… here’s North Arm Farm up in Whistler, B.C.

Charming Newberg town in Willamette Valley. This caught our eye while passing through on the search for coffee before the wines started to pour.